Bringing destreaming to life in a primary school maths class

Three experienced kaiako, Amanda Campbell, Pam Berry-Mason, and Wendy Dent brought kaiako together in May 2023 to share their experiences and practical ideas on destreaming.

In 2022, Tokona te Raki: Māori Futures Collective of Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu published a research report, He Awa Ara Rau - A Journey of Many Paths, on why we need to remove streaming in Aotearoa New Zealand. As educators, we need to ensure our tamariki have an equitable and inclusive education so that they have the opportunities to navigate the futures they desire.

In an April 2021 briefing to the then-Minister of Education Chris Hipkins and his successor Jan Tinetti, the Ministry of Education said the "evidence shows that streaming contributes to inequitable outcomes, especially for Māori learners, Pacific learners and learners with disabilities and/or learning support needs".

Streaming by definition is the practice of grouping ākonga by their perceived level of ability. From the “least likely to succeed” to the “extension” classes.

If you went to school in Aotearoa, the odds are that streaming was part of your experience. Streaming is an entrenched practice in 90% of schools in Aotearoa (The Spinoff, March 2023).

Grow Waitaha facilitator Amanda Campbell outlines the agenda for this wānanga.

Co-presenter Wendy Dent introduces herself.

Co-presenter Pam Berry-Mason shares her experiences with destreaming.

Kaiako share their proudest moments during whanaungatanga activity.

Kaiako share through group discussion how groupings happen in their kura.

Kaiako share their proudest moments during whanaungatanga activity.

Grow Waitaha facilitator Amanda Campbell shares current education research.

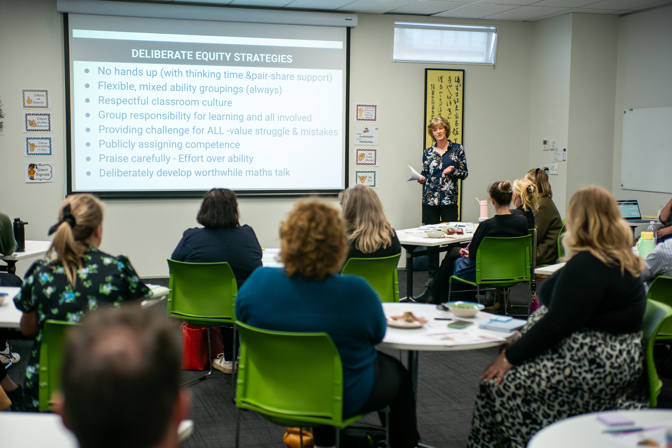

Co-presenter Wendy Dent talks about equity strategies.

Kaiako listen to presentations.

Kaiako discuss fixed and flexible groupings.

Kaiako listen to presentations.

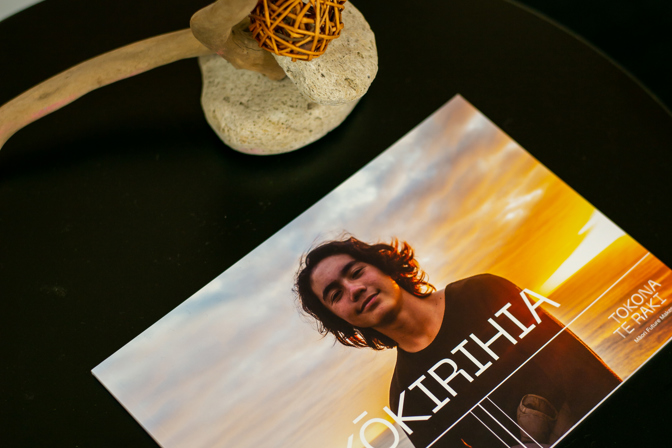

Kōkirihia - the plan to remove streaming from our schools by Tokona Te Raki.

Why should we destream?

In 2021, representatives from the Ministry of Education and the Mātauranga Iwi Leaders Group came to Tokona te Raki with a tono – to design an action plan to end streaming in Aotearoa by 2030.

Tokona te Raki states that streaming ākonga disadvantages Māori and needs to be removed.

“These practices and beliefs significantly impact learner self-esteem, self-belief, and potential, and create trauma.”

Kōkirihia - The plan for removing streaming from our schools.

Where do we start?

When ākonga begin school they are more than likely to be placed in ability groups for reading and maths. Once in these groups, whether it be the top or bottom group, they are likely to stay in this stream for the rest of their education.

“Essentially, a child’s career path and future life opportunities have been determined by the age of six.”

Kōkirihia - The plan for removing streaming from our schools.

Kaiako and leaders come together

Forty kaiako from around Ōtautahi gathered in a face-to-face workshop to investigate alternatives to ability grouping in maths.

The face-to-face workshop asked some deep-delving questions, including:

- Do you group your ākonga by ability for some curriculum areas? Which ones?

- If you group by ability, why do you do this? If not, why not?

- What are the perceived advantages/disadvantages of ability grouping ākonga?

- What are the consequences of ability grouping?

- How do ākonga view ability grouping?

The group explored ākonga voice about ability grouping that Dr Christine Rubie-Davies collected during her Teacher Expectation Project with 2,500 tamariki and 90 kaiako.

No hands up

Amanda Campbell, facilitator for Grow Waitaha, talked about the need to change student attitudes and experiences of maths before ākonga entered high school.

Amanda noticed that ākonga who entered her year 7–8 class had already decided that they could or could not do maths. It was a subject they either loved or loathed. After seeking their voice, Amanda discovered ākonga already knew whether their teacher believed they had a mathematical brain or not.

Ākonga shared experiences where the teacher only asked tamariki with their hands up for answers. They learnt quickly that if you made no eye contact and kept your head down you didn’t need to engage. The fastest child always got selected to share. Frequent statements from her tamariki were:

- “Maths is about getting the correct answer.”

- “Why do I have to share my mathematical thinking because I might be wrong?”

As a result of these findings, Amanda introduced a ’no hands up’ rule in her classroom.

Every child needed to be prepared to answer a question. Each maths session began with ‘Number Talks’, a 10-minute warm-up maths activity. No pen or paper. No hands up. Only the use of silent hand signals to communicate that mathematical thinking was taking place.

Ākonga then shared their thinking and engaged in conversations around the proposed problem. Ākonga were encouraged to have a growth mindset rather than a fixed mindset.

“The hardest thing for us as kaiako is to not communicate via speech or body language to indicate correct or incorrect thinking. I often took deep breaths and gazed out the classroom window, being very conscious of my body language, while ākonga discussed their thinking.”

Amanda Campbell, facilitator for Grow Waitaha

It wasn’t long before Amanda noticed an increase in the sound level, a positive buzz, and mathematical chat in the classroom. Using a set of classroom norms for ‘Number Talks’ ensured an engaging and accepting place to share mathematical thinking.

Mixed-ability problem-solving

The next step was the introduction of mixed-ability problem-solving. Amanda saw a need to make ‘maths real’ to give it an authentic context that ākonga found relevant and interesting.

Where possible, the problems always contained the name of ākonga, school staff, and local businesses.

“Bring their lives to maths so they can see themselves reflected in it.”

Amanda Campbell, facilitator for Grow Waitaha

Changing mixed-ability groups on a regular basis, every two-three weeks, was a key message. These groupings were formed with ākonga from middle to high ability and middle to low ability. All tasks were designed to be mathematically accessible and to have built-in extension opportunities.

Planning the format of problem-solving sessions is essential. The math concept taught earlier in the week was repeated in the problem-solving sessions at the end of the week. Complex problems taught ākonga to value struggle and failure before a sense of success. Learning is transformed through collaborative problem-solving.

Grouping ākonga in years 0-2

Guest presenter Pam Berry-Mason, learning support co-ordinator from West Melton School, shared her journey to destreaming in years 0–2.

Pam began by sharing research from Jo Boaler’s book Mathematical Mindsets. Using this book, West Melton School ensured their maths programme had the following components:

- Open up the task so that there are multiple methods, pathways, and representations.

- Include inquiry opportunities.

- Present the problem needing solved before teaching the method.

- Add a visual component and ask students how they see mathematics.

- Extend the task to make it a lower floor and higher ceiling.

- Ask students to convince and reason; be skeptical.

Boaler 2016, pages 57-91

As mathematical growth mindsets developed, the school embarked on using the DMIC (Developing Mathematical Inquiry Communities) pedagogical approach. In Aotearoa, this approach has been led by Associate Professor Bobbie Hunter, from Massey University.

Pam talked about the importance of setting up and explicitly teaching group norms for the tamariki working in flexible groupings.

Pam emphasised the importance of having five maths sessions per week. Two mixed group problem-solving sessions with six-eight ākonga enables them to work in pairs or partners of two or three. Each session was 30 minutes long. The group shared one pen and one problem-solving book.

Pam talked about the power of voice. At West Melton, all kaiako explicitly teach ‘Talk moves’, and use sentence stems. ‘Talk moves’ is a tool used to encourage ākonga to engage in rich mathematical discussions.

Pam stated, “Teachers have to STOP talking and LISTEN.”

What makes a quality maths lesson?

The second guest presenter, Wendy Dent, previously Deputy Principal at Hoon Hay Te Kura Kōaka, then shared how kaiako can embrace destreaming.

Wendy reminded kaiako of the power and responsibility that our daily decisions have on our tamariki.

- Every decision, interaction, and action has an impact negative or positive.

- We can build or destroy a child’s maths identity through our language (spoken & unspoken), and actions, such as grouping.

- Position all children to be equally worthy and valued:

- by themselves

- by their peers

- by their teacher.

Using flexible/mixed ability groupings is a deliberate equity strategy. Having these groupings allows every class member to have equal access to learning, feel valued, and feel supported.

Wendy stressed the importance of:

- a 'no hands up' rule to provide all ākonga with thinking time

- flexible/mixed ability groupings

- a respectful classroom culture

- challenge for all ākonga

- valuing struggles & mistakes

- praising carefully; always praise effort over ability

- deliberately developing worthwhile maths talk.

Wendy talked about the importance of having school-wide consistency.

“Tamariki experiencing success, loving maths and feeling good about themselves as mathematicians is a worthwhile goal.”

Wendy Dent, presenter

Top tips

- Know your learner:

- Use what you know to make context relevant.

- Bring their lives to maths so they can see themselves reflected in ‘school maths’.

- Make learning accessible and challenging.

- Promote collaboration and maths talk.

- Don’t let mathematical discussions be driven by the fastest ākonga (the ‘always first’ kids).

-

Do use think time, pair share and no hands up.

-

Don’t use flashcards, speed competitions, or timed tests. Praising speed gives the wrong message about what’s important. If we value fast computation, we exclude deep, slower thinkers.

-

Do value creativity, different ways of thinking and explaining.

Additional resources

Here are some additional resources to assist you in building your awareness and alternatives to streaming:

Jo Boaler - Mathematical Mindset books

Jo Boaler https://www.youcubed.org/

Destreaming in Secondary Schools Aotearoa NZ (event recording part 1)

Destreaming in Secondary Schools Aotearoa NZ (event recording part 2)

Kōkirihia - The plan for removing streaming from our schools